This essay was originally written in April 2021 for a course on Public Memory, during my work toward an MA degree in Cultural Studies at the University of Winnipeg.

Precis

I begin this research essay by considering how Cooper's practice (both scholarly and as a poet) relates to memory studies. In the second part of the essay, I examine several of Afua Cooper's poems from the 2020 book Black Matters as examples of "counternarrative" (Cooper "Constructing" 45-46). I will argue that these counternarratives enacts historical events of diasporic Black life (in Canada, the Caribbean and elsewhere) as lived experiences, in a direct response to the erasure of that life by the forgetting machine of white settler colonialism. My general methodological approach will be interdisciplinary, linking literary studies, cultural studies and memory studies, with attention paid to the intersectionality (Black, feminist, decolonial) of Afua Cooper's poetry practice. My main method of data collection will be textual analysis, although I will touch on an example of Cooper's recorded poetry as well, and will make her work's performative aspects part of my analysis.

The Essay

I began considering Afua Cooper's poetry, specifically those poems which source history and memory, as a potential object of analysis when I attended her virtual poetry reading of 4 February 2021 ("Black Writing"). During the question and answer session following her reading, Cooper said that Black lived experience could be better conveyed through poetry or fiction, rather than through nonfiction, simply because there is so little Black presence in the historical archives, and when there is, it is often filtered through the words of the white dominating classes. She related this to Aimé Césaire's concept of the "forgetting machine" of colonialism (Tinguely). It's an indication of Cooper's longstanding concern with history and memory. Consider her choice of title for her 1992 collection, Memories Have Tongue. It takes its title from a poem in which she revisits the memories of her grandmother, as a means of probing aspects of Jamaica's cultural and social history ("Memories").

I first heard one of Afua Cooper's poems in the late 1980s, when I was deejaying a radio show on Halifax's CKDU FM. I selected "Christopher Columbus" from a cassette intriguingly entitled Your Silence Will Not Protect You, which featured a heady mix of Indigenous and Black poets and musicians from Canada and beyond. Cooper's piece, dub poetry delivered with backing percussion, addressed the extermination of the Indigenous Arawak population of Jamaica in the early phases of colonialism.

In the poem, she speaks of her experience as "a little girl in grade four," a Jamaican child learning the sanitized, heroic version of the Columbus story, and contemplating the marble statue of Columbus that "stands on the hill facing the sea," commemorating the "discovery" of Jamaica in 1494.

His hand rests on the hilt of the sword

I walk beneath the statue

His feet crush my brain

His sword cuts open my womb

I flee I flee

From beneath his shadow

Leaving my blood on the ground

Then she writes from the perspective of a young woman now living in Canada of the late 1980s. On revisiting Jamaica, she says, "I look again at the statue, and marvel that even today we still honour our conqueror" ("Christopher Columbus").

Cooper's poem can be understood as a response to the settler colonial narrative of her birthplace. Although profoundly different places, Jamaica and Canada share this legacy of settler colonialism, and are linked by complex networks of trade, migration and imperialism that have developed over centuries. Cooper writes, in her 2000 essay, "Constructing Black Women's Historical Knowledge,"

From the days of New France important trading links existed between the Caribbean and Canada. Indeed, Caribbean slaves for at least two centuries survived on salted cod and wheat flour from what is now Canada. The Caribbean supplied rum, sugar, molasses, and slaves in return. This arrangement continued under the British regime and intensified during the period of capital accumulation and imperialism with the establishment of Canadian banks, insurance companies, and multinationals in the Caribbean (42).

Whether in Jamaica or in Canada, a statue of Christopher Columbus can be understood to be "part of the political infrastructure of settler place-making" (Rose-Redwood & Patrick).

Since moving to Canada as a child, Cooper has become Dr. Afua Cooper, "a historian, poet, and creative writer whose research focuses on slavery and the abolitionist movement in Canada and beyond" (McNutt). As an early example of the poetry of Afua Cooper, "Christopher Columbus" works as a counternarrative, which she defines as a narrative of the oppressed which questions the validity of the narrative of the oppressor (45-46). Counternarrative is a direct intervention in the dominant narrative of settler colonialism, one which unsettles "official" public memory, such as the public memory embodied in the statue of Christopher Columbus in Jamaica. The poem "Christopher Columbus" can be seen as entering into conversation with the remembered monument, in much the same spirit that vandalism of statues can be understood as occurring in dialogue with the statues' settler colonial narrative (Rose-Redwood & Patrick).

This sense of a dialogue is elaborated by Roger I. Simon, Sharon Rosenberg, and Claudia Eppert in "Between Hope and Despair," when they write, "Quite counter to epistemic traditions that grasp consciousness as singular and learning as taking place 'within' individuals, we view historical consciousness as always requiring another, as an indelibly social praxis, a very determinate set of commitments and actions held and enacted by members of collectivities" (2). Even early in her career, Cooper's understanding of her own poetry practice already extended beyond the bounds of a simple literary practice. "When I read and write poetry I am engaging not only in literary production but in cultural and community work as well" ("Finding My Voice" 304). Here, she speaks of a practice that weaves together "the lyrical, the spiritual, and the historical" (303), using history as "a rich poetic source" in order to discover "my family, my country, my race, and later on, my gender," and ultimately, to work toward social change (304).

In other words, Cooper isn't simply a history professor who dabbles in poetry. "'I see myself as a public intellectual, as an organic intellectual,' she says. 'So I don’t see my work as something that stays within the academy; it has to be shared'" (Ryan). Her's is a poetic practice of remembrance, a project that grounds itself in a wider movement of Black cultural producers who combat Canada's cultural amnesia around issues of slavery, systemic racism and the politics of exclusion. In his book Black Like Who: Writing Black Canada, Rinaldo Walcott examines this movement through studies of poets like M. Nourbese Philip and Dionne Brand, as well as film-makers, rap artists and Black pop artists. He writes, "The invention of a grammar for black in Canada that is aware of historical narrative and plays with that narrative is crucial in the struggle against erasure" (156).

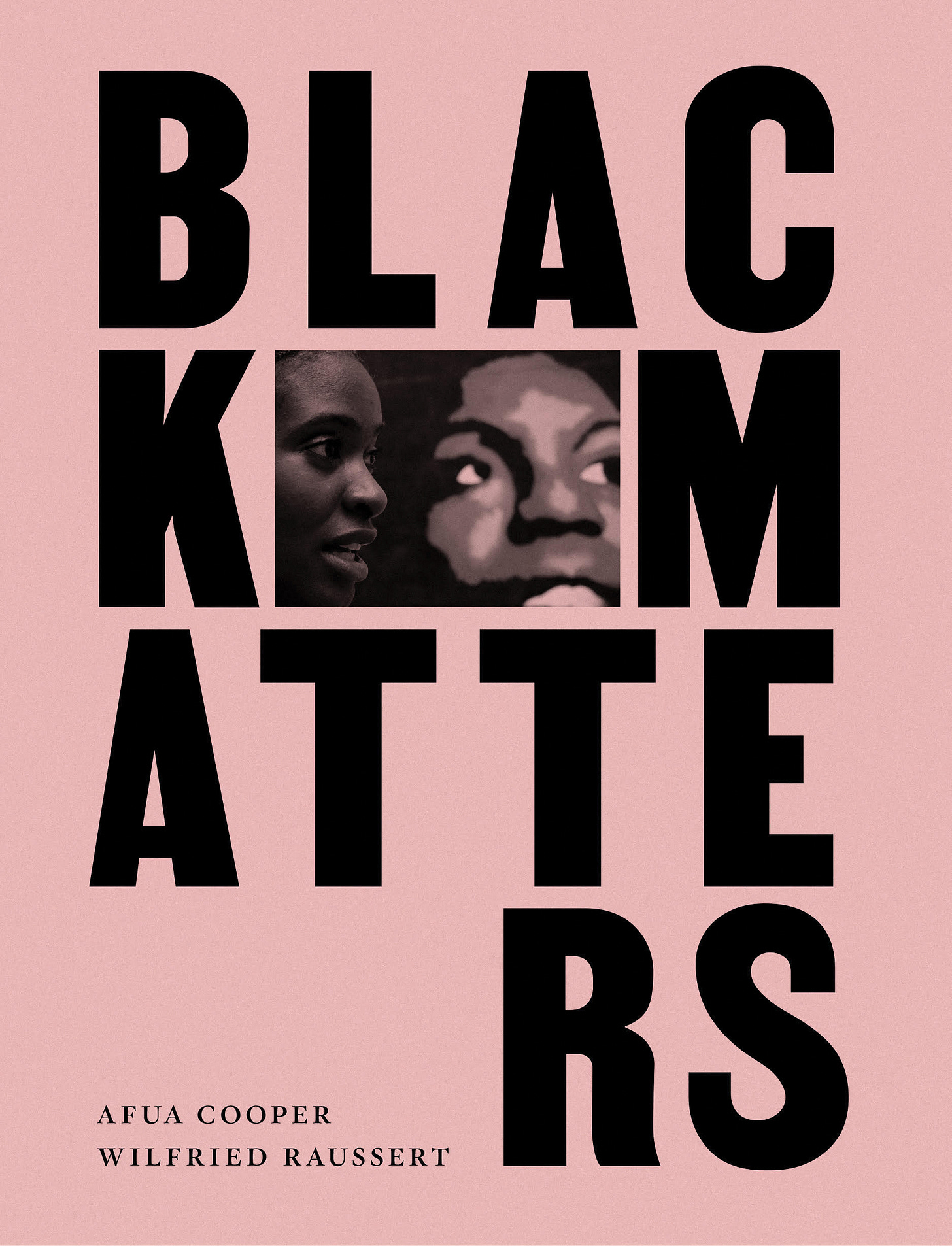

In 2020, Afua Cooper and the photographer Wilfried Raussert collaborated on a book of poetry and photos. It's title, Black Matters, makes a clear connection with the Black Lives Matters protests that have had such a profound impact on public awareness following the killing of George Floyd on May 25 of 2020. The interplay between poetry and image was a productive one, according to the book's introduction. "Both text and images eventually coalesce around such themes as marronage, parenthood, time travel, grief, fractured ancestry, spiritualities, diasporas, love, resistance, and resilience. In this book, poems and images fuse into their desire to celebrate Blackness as public expression of human relations, aesthetics, and politics" (10).

Cooper's poems in Black Matters frequently hark back to historic moments of Black experience in Canada. "While the images speak to the presence of Black people in contemporary societies, they often engage past historical and mythological epochs. The past and present comingle" (7). I have chosen five poems from Black Matters that vividly evoke historic events involving Black subjects, both in Canada and beyond: "John Ware: Magician Cowboy" (14-23), "Fugitive" (24-27), "Jupiter Wise" (29-30), "Uncles" (31-32) and "A World Greener Than Eden" (67-71).

Each poem serves as a counternarrative which makes Black agency and Blackness itself visible in the context of what Helen Vosters calls "white Canadian settler-colonial nationalism" (10). In their conversation with Raussert's photos of contemporary Black life, the poems "time-travel" between the past they reconstruct, and the Black visibility of our current moment. The wonder the poems evoke by making the historically invisible Black presence visible to the reader (and to Cooper's audience when she performs her poetry) is the result of what Vosters calls a "praxis of redress." A "praxis of redress" describes performances "that work to unbecome the dominant narratives of Canadian nationalism and the fictive innocence of our imagined nation" (11).

Cooper enters into a praxis of redress through the intent of honouring the spirit and agency of historic figures who might otherwise remain invisible to the dominant white Canadian public. In the introduction to Black Matters, this facility is called "the poet's historical memory" (7). As a starting point, she draws on her doctorate in Black history, and her research into archival traces of historic Black lives in Canada, but it is her creative practice as a poet through which she is able to articulate what Angela Failler describes as, "those traces of trauma that remain largely ungraspable but nonetheless bear upon the force of the past for the present and future." In her essay, "Remember Me Nought," Failler argues that artworks, "have the capacity to evoke experiences or expressions of traumatic pasts that formal and official efforts [...] cannot—namely, the less tangible effects of trauma that linger as unconscious desires, memories, and unfinished grief" (117).

Camille Turner, whose performance practice draws on Afua Cooper's research (59), writes, "there is much work to be done in the field of recovering and reconstructing Canada's Black histories as well as confronting the mechanisms through which they are absented and displaced" (55). Cooper herself writes,

It is instructive to note that from the beginning of what we now call Canada, there was a Black presence. Canada evolved from settler colony to nation, based on the appropriation of Native land, and became incorporated from its early colonial period (both French and British) into an international capitalist order. And through these myriad incarnations of Canada, Black people have been part of its history though this knowledge, given the history of their subordination in Canada, has been submerged ("Constructing" 40).

One trauma that has remained mostly absent from white Canadian public memory is that of Black slavery, which Katherine McKittrick calls, "a denied and deniable Canadian institution" (Demonic 91). To date, there is no national memorial to mark the enslavement of African people in Canada (Government). Cooper's poems "John Ware: Magician Cowboy," "Fugitive," and "Jupiter Wise" all explicitly address this "deniable" institution, and its definition of slaves as nonpersons and chattel.

John Ware was an emancipated slave from South Carolina who became a Black cowboy in Texas. He roamed the plains from Montana up to Alberta, where he became an expert horse-breaker, married, and settled near a town called Brooks. The poem retains traces of the archive: for example, "In Calgary / the newspapers called you the greatest cowboy" (23). But Cooper also feels free to embellish, enlarge and embody her subject in a way she's not able to do through the discipline of historical research. "... who were his parents? From where did they come? The poet's imagination then took flight and travelled with Ware to ancient kingdoms in what are now Ghana and Nigeria" (7).

Upon listening to Afua Cooper perform "John Ware" during her virtual reading, I felt surprise that I'd never heard of this man before. Katherine McKittrick reflects on this sort of reaction to Black history in Demonic Grounds: "The element of surprise, then, holds black Canada in tension with the nation’s ceaseless outlawing of blackness: blackness is surprising because it should not be here, was not here before, was always here, is only momentarily here, was always over there (beyond Canada, for example)" (93). In her poem, Cooper writes, "John Ware / cowboy magician / part of the brotherhood of Black cowboys / who have been erased from the history of the West" (15).

In "Fugitive," Cooper writes of Peggy Pompadour, who also figured in her scholarly essay, "Constructing Black Women's Historical Knowledge." Cooper writes, "The main source for Peggy's history is the Russell papers, namely the documents of Peter Russell and the diary of Elizabeth Russell." It is in relation to the story of Peggy that Cooper raises the question of narrative versus counternarrative. "The question of voice is central here. The master class is the one who is telling us what the slaves are like. There is no counternarrative from Peggy or her family. This raises the question of the validity of the oppressor's voice when talking about the oppressed" (45-46).

In the poem "Fugitive", Cooper chooses to damn Peter and Elizabeth Russell with their own words, describing the escalating acts of inhumanity toward Peggy and her children with the language of the oppressor. "Because no one wants her / Peter has to keep her in jail / he resents paying the jailer's fee / If only this mean slave / would behave!" (26). Hearing Cooper perform this poem during her virtual poetry reading allowed the audience to experience the cruel irony of a Black woman delivering her lines in the arch tone of a racist upper class Torontonian, one who treats Peggy's children as property. "I have already gifted my goddaughter / Elizabeth Dennison / with Milly and Amy" (27). In Black Matters, the poem includes a reproduction of the newspaper ad Peter Russell took out, offering Peggy for sale.

Voice plays an important part in "Jupiter Wise" as well. It tells the tale of another recalcitrant slave, who is captured once in his attempt to flee from Prince Edward Island, and upon being sentenced to "West Indian slavery," escapes again, "to Nova Scarcity / lived there as a Maroon with your wife" (30). Cooper writes in the voice of a strong Black woman of today, exhorting the ghost of Wise to "Arise!" and tell his story. She shifts from standard English to Jamaican patois halfway through the poem:

Jupiter

let me see your disguise

play fool fi ketch wise

you with the patoo eyes

that you use fi hypnotize

white mask, Black skin

tink seh you a jinn (30)

This shift reinforces a sense of kinship between the poet and her subject, an emotional connection that spans the centuries separating them. Her words valourize his struggle for freedom and his bravery in the face of potentially lethal oppression.

The poems "Uncles" and "A World Greener Than Eden" return the reader to the autobiographical reminiscence used in Cooper's earlier poems, "Christopher Columbus" and "Memories Have Tongue." With "Uncles," which she describes as, "a tribute to all uncles, brothers, sons, dads who must travel far and wide as migrant labourers to work in agro-industries to enrich corporations, but also to reproduce the material lives of their own families" (9). In the first two sections of the poem, she describes brutal working conditions in the cane fields of Louisiana and orange groves of Florida, and closes each of the sections with a line of patois that might have been delivered by the men themselves: "man did tink seh slavery done" (31); "Man sweat for penny wages, tink him gwine die" (32). Here, Cooper makes the connection between the slave system of antebellum America, and wage slavery under contemporary conditions of neoliberal capitalism.

In "A World Greener Than Eden," Cooper includes a subtitle at the beginning of the poem: "MY FATHER PLANTED A PROVISION GROUND" (67). It is an appreciation of "her father's and grandfather's roles as horticulturalists and providers for their families" (9), in which she draws an image of Black masculinity that is nurturing and positive, in opposition to the negative stereotypes engendered by narratives of white supremacy. It is a list poem, cataloguing the many vegetables grown by her father, who "always praised the soil" (68); this reminiscence leads Cooper to recall her grandfather's horticultural efforts in Jamaica, "Decades before" (69), planting citrus groves, coconut trees, sugarcane. Her conclusion unites these two generations:

These men built a well,

with a spout pointing

In each of the four directions,

that carried water

to irrigate

the crops they planted (70-71)

In "Rebellion / Invention / Groove," her study of Sylvia Wynter's unpublished book Black Metamorphosis, Katherine McKittrick traces Wynter's argument concerning Black cultural production:

[...] she argues that the perspectival economic imperialism of the planet, and attendant racial processes such as plantation slavery, produced the conditions through which the colonized would radically and creatively redefine—reword, to be specific—the representative terms of the human. It is suggested, therefore, that such inequitable systems of knowledge can be, and are, breached by creative human aesthetics (80-81).

Cooper's poetics have developed in the context of a whole community of Black cultural workers struggling against what Turner characterizes as a "national mythology of 'two founding races'" which "sustains Whiteness as central and normative and renders the presence and contribution by everyone else, marginal, and recent or absent altogether" (55). This is the context in which Cooper's poetry can be understood as flowing from the deep Black tradition to "reword [...] the representative terms of the human," to "rehumanize" the dehumanized stereotypes of Blackness generated by the narrative of white supremacy. In her role of "public intellectual" she intervenes in the Canadian mythology with poems that vividly recover fragments of Black history from the national unconsciousness.

For a Black audience, these poems will affirm their experiences, and present a counternarrative to the mythology of Whiteness. In the words of McKittrick, "the repression is overturned" ("Demonic" 100), providing welcome relief from the narrow and narrowing dominant ideology. Cooper's poems, in the larger context of Black scholarship and cultural production across Canada, do the work in the absence of a national memorial for the enslaved, or a national day celebrating the abolition of slavery in Canada.

For white audiences, these poems must be understood as aspects of a "difficult remembrance," in the words of Simon, Rosenberg and Eppert (1). They can become part of "a hopeful practice of critical learning" (6), in which one engages with "the struggle to work through one's own affiliations with and differences from the 'original' narrative or memory" (7). Ideally, it will bring white audiences to a fuller awareness of how settler colonialism is foundational, woven into the very fabric of the Canadian state, and demanding an ongoing process of relearning and repositioning of oneself within this new understanding. It is a difficult process, but ultimately a hopeful one.

Remembrance is, then, a means for an ethical learning that impels us into a confrontation and "reckoning" not only with stories of the past but also with "ourselves" as we "are" (historically, existentially, ethically) in the present. Remembrance thus is a reckoning that beckons us to the possibilities of the future, showing the possibilities of our own learning (8).

Works Cited

"Black Writing in Canada series continues." University of Winnipeg website, news page. 26 January 2021.

Cooper, Afua. "Christopher Columbus." Your Silence Will Not Protect You, Produced by Dubwise, Maya Music Group, 1989. Cassette recording. Texts transcribed from audio by Tinguely.

Cooper, Afua. "Finding My Voice." Caribbean Women Writers: essays from the first international conference. Calaloux Publications, 1990, pp. 301-305.

Cooper, Afua. "Memories Have Tongue." Canadian Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries, 2000.

Cooper, Afua. "Constructing Black Women's Historical Knowledge." Atlantis, vol. 25 no. 1, Fall / Winter 2000, pp. 5-17.

Cooper, Afua and Wilfried Raussert. Black Matters. Roseway Publishing / Fernwood Publishing, 2020.

Failler, Angela. "Remember Me Nought: The 1985 Air India Bombings and Cultural Nachträglichkeit." Public no. 42, "Traces" issue, Winter 2010, pp. 113-124.

Government of Canada, "The Enslavement of African People in Canada (c. 1629–1834)." Parks Canada, 31 July 2020.

McKittrick, Katherine. "Nothing's Shocking: Black Canada." Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, University of Minnesota Press, 2006, pp. 91-119.

McKittrick, Katherine. "Rebellion / Invention / Groove." Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism no. 49, March 2016, pp. 79-91.

McNutt, Ryan. "Heritage, leadership and pride: The work of Afua Cooper, the James R. Johnston Chair in Black Canadian Studies." Dalhousie News, 13 February 2015.

Rose-Redwood, Reuben and Will Patrick. "Why activists are vandalizing statues to colonialism." The Conversation, 17 March 2020.

Simon, Roger I., Sharon Rosenberg, and Claudia Eppert. "Introduction – Between Hope and Despair: The Pedagogical Encounter of Historical Remembrance." Between hope and despair: pedagogy and the remembrance of historical trauma. Roger I. Simon, Sharon Rosenberg, and Claudia Eppert, eds. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2000, pp. 1-8.

Tinguely, Vincent. "Afua Cooper." 4 February 2021. Notes taken during a virtual poetry reading.

Turner, Camille. "Miss Canadiana Confronts the Mythologies of Nationhood and the im/possibility of African diasporic memory in Toronto." Caribbean In Transit, vol. 1, no. 2, March 2012, pp. 52-60.

Vosters, Helene. "Introduction – Lest We Forget: The Contested Terrain of Canadian Social Memory." Unbecoming Nationalism: From Commemoration to Redress in Canada, University of Manitoba Press, 2019, pp. 1-28.

Walcott, Rinaldo. Black Like Who: Writing Black Canada, second revised edition. Insomniac Press, 2003.